Sometimes you have to say “No” to yes/no questions. While yes/no questions are easy to write, they are not always the right question for a task. In part, this is because respondents tend to be agreeable and often select “Yes” by default. (This is called acquiescence response bias, an effect that has been replicated in over a hundred studies.) One option to minimize the effect of acquiescence bias is to write longer descriptions of what yes and no mean.

•Have you ever purchased an app for your smartphone?

○Yes, have purchased an app for my smartphone

○No, have never purchased an app for my smartphone

This also squares with seminal eye-tracking research done by Element 54, which showed that people’s eyes often jump first to where they are asked for a response – the choice list – then glance back at the question.

•Have you purchased an app for your smartphone in the past 30 days?

○Yes, have purchased this in the past 30 days

○No, have not purchased this in the past 30 days

Have you purchased software for a laptop or desktop that comes with a companion mobile app in the past 30 days?

○Yes, have purchased this in the past 30 days

○No, have not purchased this in the past 30 days

•Have you purchased an accessory for your smartphone in the past 30 days?

○Yes, have purchased this in the past 30 days

○No, have not purchased this in the past 30 days

This is called a forced-choice battery, as participants are forced to answer each item. A more streamlined way to ask this is as a “Choose all that apply question”:

•Which, if any, of the following have you purchased in the past 30 days?

○A smartphone app

○Software for a laptop/desktop that comes with a companion mobile app

○A smartphone accessory

○None of the above

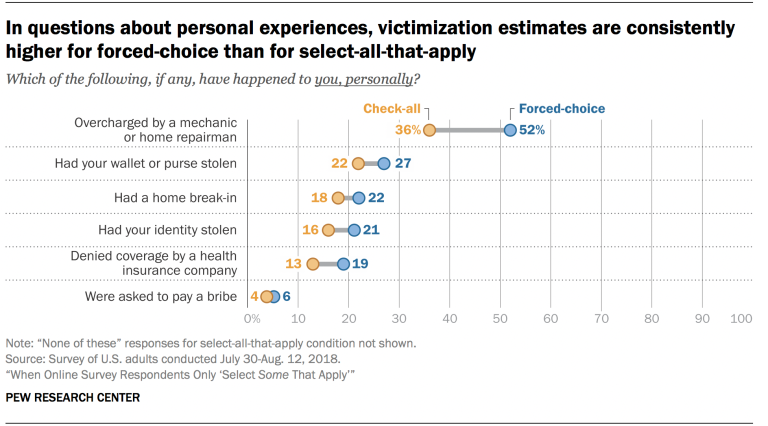

The two approaches do not produce identical results, however. While Pew Research found in A/B tests that the relative frequency order was consistent between the forced-choice battery and a corresponding all-that-apply question, the all-that-apply question produced lower rates for each item. Participants treat such questions as “select some that apply,” in Pew Research Center’s memorable phrase, and an all-that-apply question will report lower percentages than a series of forced-choice questions. In part, this happens because as participants read surveys, they often skim the text, looking for the most salient options. This is called satisficing.  Note that a series of yes/no questions is considered more cognitively difficult than an all-that-apply question. The good news is participants are forced to review and respond to each line item, while they may glance over an all-that-apply list to the find those that are most salient to them. Pros and cons:

Note that a series of yes/no questions is considered more cognitively difficult than an all-that-apply question. The good news is participants are forced to review and respond to each line item, while they may glance over an all-that-apply list to the find those that are most salient to them. Pros and cons:

•The forced-choice battery is more accurate than an all-that-apply question

•The battery takes more room to display in either a paper or online questionnaire

•The battery takes longer to answer

•The battery is more tedious to answer

•The all-that-apply question works better in screeners, where it can minimize screener bias.

Tips for writing the yes/no options:

You don’t need to completely restate the question. For instance:

•In the last month, did you attend religious services in person at a church, synagogue, mosque or other house of worship?

○Yes, attended religious services in person in the last month

○No, did not attend religious services in person in the last month (source: Pew Research)

You don’t need to include a pronoun (the above option wasn’t “Yes, I attended…”)

You can use “this” instead of a longer recap of the question:

•Do you think the United States has a responsibility to provide financial assistance to developing countries to help build renewable energy sources and move away from fossil fuels?

○Yes, the United States has this responsibility

○No, the United States does not have this responsibility (source: Pew Research)

Originally published 2022-03-31. Updated 2022-04-21 with yes/no tips.