Bipolar scales such as Completely satisfied to Completely dissatisfied tend to be overused and misused in survey research today and can often be replaced with unipolar scales such as Completely satisfied to Not at all satisfied. And even when bipolar scales are more appropriate, they are often asked in older formats that are less reliable.

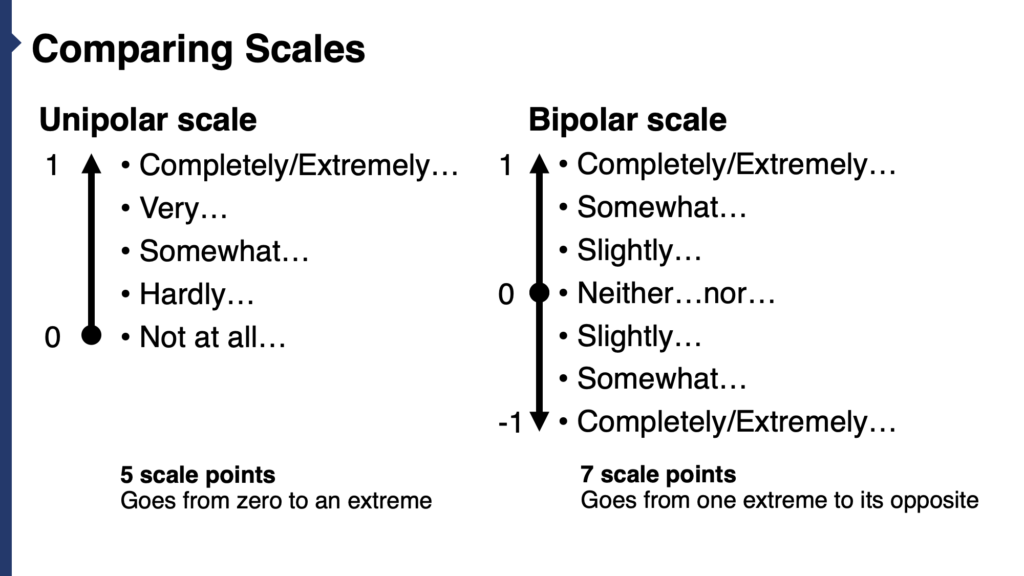

First, what is scale polarity? A bipolar scale contrasts opposites, while the unipolar scale focuses on one attribute.

When coded behind the scenes, a bipolar scale might be coded as -1 (e.g., Completely dissatisfied), -0.67, -0.33, 0, 0.33, 0.67, 1 (Completely satisfied), with the ends having the same absolute value but different numeric signs, where a unipolar scale might be coded as 0 (Not at all…), 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1 (Completely/Extremely). For instance, for a likelihood scale, think of Not at all likely as corresponding to 0% of the time, Somewhat likely to 50% of the time, and Completely likely to 100% of the time.

The Difficulty with Bipolar Scales

Here are some of the issues with bipolar scales:

- Because bipolar scales contrast two opposites, they require more cognitive effort for respondents to evaluate than unipolar scales. Respondents must decide which of two extremes to select (or the midpoint), then to what degree they tend towards that extreme. For a unipolar scale, respondents are just assessing the extent.

- The midpoints of bipolar scales can be a point of confusion, open to different interpretations by different respondents. Sometimes a choice like Neither boring nor interesting is selected as a “don’t know” response, while to other respondents it might mean “neither” (“neutral”) or it might mean “boring in some ways and interesting in others.” (This example is from “The Science of Asking Questions” by Nora Schaeffer and Stanley Presser.) (Despite this, Wang and Krosnick find bipolar scales without midpoints to be less reliable.)

- As with the Boring/Interesting scale, survey authors can go astray by presenting bipolar questions where the endpoints are not pure opposites (e.g., Cheap to Expensive, with cheap having connotations of low quality in addition to low price).

- Better-formed bipolar scales are longer and require more reading than unipolar scales. While bipolar scales often are presented using 5-point scales (e.g., Completely satisfied, Somewhat satisfied, Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, Somewhat dissatisfied, Completely dissatisfied), 7-point scales are more reliable (and minimize context effects from earlier questions). Yet it turns out that asking bipolar scales as three or four questions is more reliable still (see below).

- Bipolar scales can also complicate factor analysis, according to Wijbrandt van Schuur and Henk Kiers (1994).

Replace Bipolar Scales with Unipolar Scales When Possible

Bipolar satisfaction, importance, and likelihood scales can easily be replaced by unipolar scales that will be more reliable and easier on the respondent. This is a version of those as unipolar scales:

- Extremely/Completely satisfied/important/likely

- Very satisfied/important/likely

- Somewhat satisfied/important/likely

- Hardly satisfied/important/likely

- Not at all satisfied/important/likely

Some other scales can be re-phrased as unipolar scales as well. Dagmar Krebs found no impact on reliability between unipolar and bipolar scales for an agreement scale (Not at all agree to Strongly agree, vs. Strongly disagree to Strongly agree), although you should use construct-specific scales rather than agreement scales wherever possible. (Earlier work by Krebs and Jürgen Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik also didn’t find significant differences between scales based on scale polarity.)

Use Bipolar Scales for Quantity, Liking, and Word-of-Mouth Measurement

Bipolar scales work well for changes in quantity and attitudes about changes in quantity. A bipolar scale works well for predicting positive vs. negative recommendations of brands (see Schneider, Berent, Thomas, and Krosnick; 2018).

Semantic differentials are a form of question battery where every item uses a different bipolar scale, with only labeled endpoints. For instance, sweet vs. bitter, healthy vs. unhealthy, and affordable vs. expensive to rate a presented concept for a grocery item. The endpoints used in such scales are sometimes not true opposites.

Break Bipolar Scales into 3 or 4 Questions

Malhotra, Krosnick, and Thomas (2009) show that breaking bipolar scales into multiple questions improves criterion validity over using single questions. For instance, instead of using a 7-point bipolar scale, use these three questions:

- “Do you think that the amount of money the federal government spends on the U.S. military should be increased, decreased, or neither increased nor decreased?”

- [if answered increased] “Do you think that the amount of money the federal government spends on the U.S. military should be increased a lot, a moderate amount, or a little?”

- [if answered decreased] “Do you think that the amount of money the federal government spends on the U.S. military should be decreased a lot, a moderate amount, or a little?”

Those who said “neither increased nor decreased” aren’t asked a followup question, as it does not improve validity.

Here’s an example liking question referenced in the same paper: “When you think about George W. Bush as a person, do you like him, dislike him, or neither like nor dislike him?” followed up with “Do you [like/dislike] George W. Bush a great deal, a moderate amount, or a little?”

A common bipolar scale ranging from “Strong Democrat” to “Independent” to “Strong Republican” has proven to be less reliable, confounding partisan identification and independence, with a separate follow-up question needed to sort Independents into “lean Democrat” or “lean Republican.”

While each of these examples use three to four questions to capture attitudes, those attitudes are then measured and reported on an underlying 7-point scale for analytical purposes. (Again, this scale outperformed 3-, 5-, and 9-point scales.) So the answer to the military question is analyzed as with this scale:

- Decreased a lot

- Decreased a moderate amount

- Decreased a little

- Neither increased nor decreased

- Increased a little

- Increased a moderate amount

- Increased a lot

Another alternative, if detailed correlations between variables isn’t required, is to limit bipolar questions to the three choices of that first question: “Do you think that the amount of money the federal government spends on the U.S. military should be increased, decreased, or neither increased nor decreased?” This question alone may be sufficient for newsmaker studies, for instance.

Conclusion

Although commonly used on questionnaires, the bipolar question is often misused. Replace it with a unipolar question where possible. Where a bipolar scale is the best, and the question is central to the goals of the research, ask it as a series of three questions (or four, in the case of partisan identification).

First published on July 25, 2017, but updated with better examples.